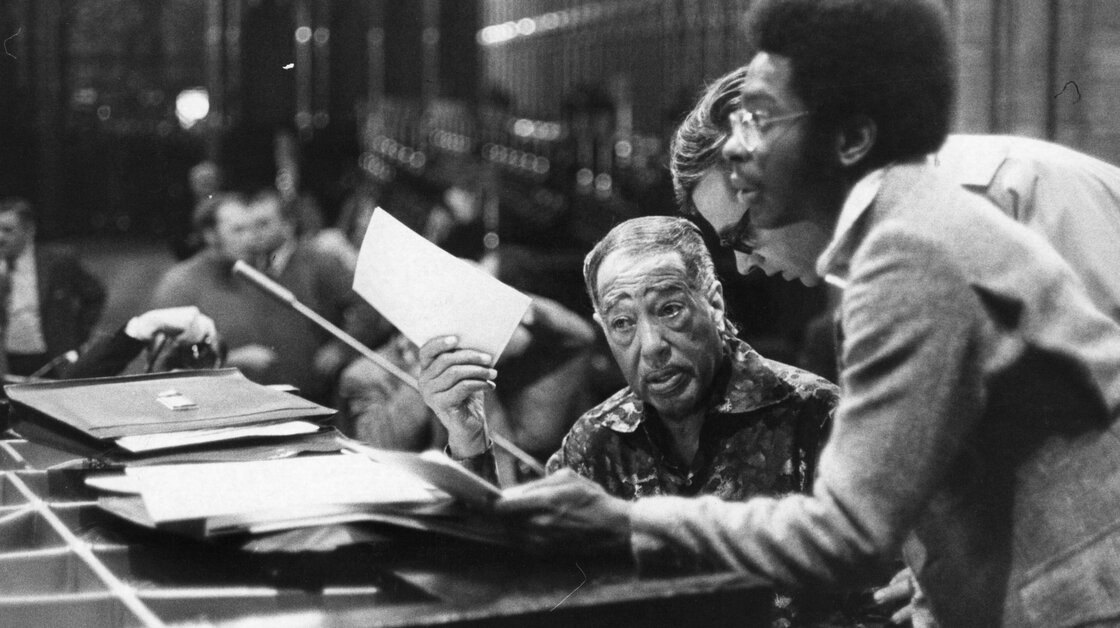

“Killer” Ray Appleton, a veteran drummer with the wisdom of experience and ageless swing.

Jimmy Katz/Courtesy of the artist

I’ve been listening to two very good new albums led by drummers. After learning that both men are in their early 70s, I can’t help but wonder how I process that fact in what I hear.

“Killer” Ray Appleton (b. 1941) and Barry Altschul (b. 1943) practice different styles. But they both came of musical age in the hard-bop era, spent many years living in Europe and eventually returned to New York. In other words, they’ve each got a lot of experience.

The new album from Appleton, Naptown Legacy, which is old-school in almost all good ways. It’s unselfconscious, head-solo-head hard bop for three tightly-arranged horns and rhythm section. (Tenor saxophonist Todd Herbert even affects a lot of Blue Train-era Coltrane mannerisms, a bit disconcerting for my taste.) It’s a program of standards and tunes by Appleton’s fellow Indianapolis natives Wes Montgomery, Freddie Hubbard and J.J. Johnson. It wouldn’t be out of place on Blue Note or Riverside c. 1961, and that’s apparently the intended effect: Even the cover art, track listing, slim bi-fold packaging and liner notes are formatted to evoke the LPs of the era.

You get the sense that this is Appleton’s bread and butter, and highly present in the mix, he struts all over this record. His fills aren’t virtuosic in a jaw-dropping way; on tunes like “Backlash” and “Fatback” he’s happy to take a good beat and play it essentially the entire song. (Does anyone do that any more in jazz?) Simplicity can be deceptive, though, and attention to detail is where Appleton shines. His splaying ride cymbal, his ease with accents and commentary, his hookup with conguero Little Johnny Rivero — these sorts of things set this music apart from its imitations. Could this be attributed to finely-honed touch and timing cultivated over decades, a sense of swing deeply embedded from a young age? Whatever it is, it reminds me how infectious the heralded recordings of a half century ago remain today.

Altschul is often thought of as belonging to a different era and community. His early recordings were with musicians like Paul Bley, Sam Rivers, Anthony Braxton and the band Circle (with Braxton, Chick Corea and Dave Holland). Altschul’s known for his avant-garde or free jazz playing — specifically, for melding a driving bebop pattern with further out improvisations, an idea known as freebop. On his new trio recording, bassist Joe Fonda and tenor saxophonist Jon Irabagon are game, and they straddle the lines between uptempo bebop and free improvisation with authority.

The 3dom Factor is ultimately Altschul’s showcase,which he uses to demonstrate a wide range of styles. His funk groove (“Papa’s Funkish Dance”) and old-time shuffle (“Natal Chart”), his literal bells and whistles, his sense for loosening or unwinding a beat. It’s his music, too: The band reinterprets original compositions from throughout his discography (and Carla Bley’s “Ictus”). They’re tuneful and worth paying attention to, although he still doesn’t really consider himself much of a composer:

Cover art to Barry Altschul’s new album, The 3dom Factor.

TUM Records

I’m a drummer, man. All I want to do is play. So any music I write, or that I thought about writing, or that I contribute to a band, was to stimulate a playing attitude, someplace to have fun in, to maybe be interesting, to be challenging, but I do not try to make a mark as a composer.

That’s from an extensive recent interview with fellow percussionist Harris Eisenstadt. Like Appleton, Altschul is quite happy playing others’ music, and doesn’t prioritize leading a band, so much so that he hadn’t recorded as a leader since 1985.

In my mind, these two albums are overdue returns, career-portrait recitals from veteran masters. Their experience isn’t the only lens we have into these artists, but it seems like an important one here. Do you have any favorite albums by elder statesmen and women in jazz? Let us know on facebook. Just search for kjemjazz.