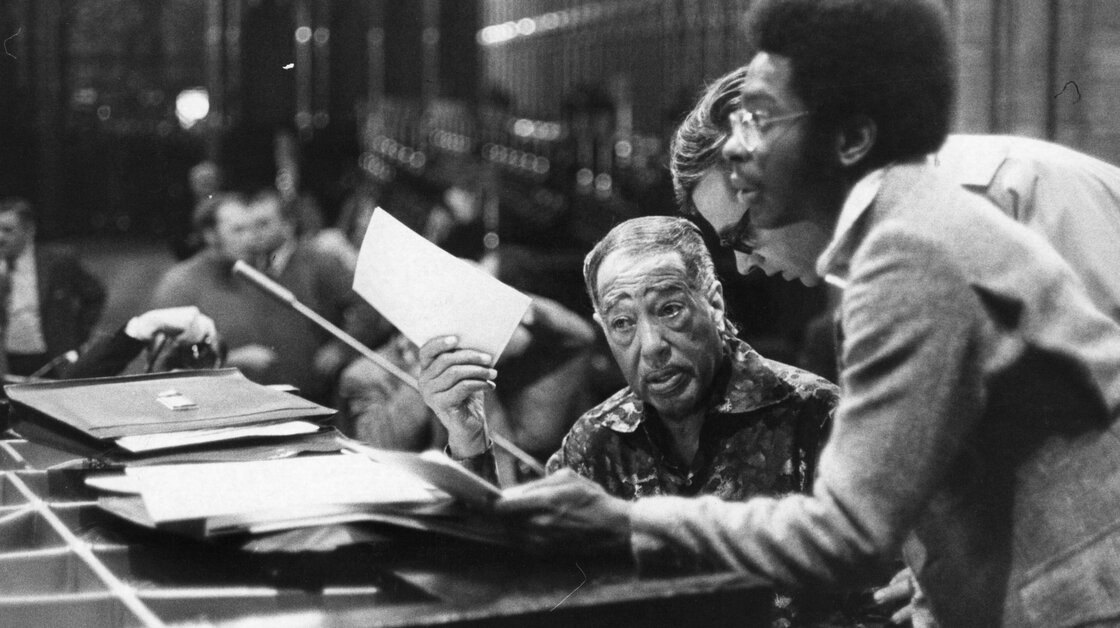

Kenny Burrell performs at his 80th birthday concert in 2011.

Reed Hutchinson/UCLA

Just before 11 o’clock on a crisp Monday night in Hollywood, 82-year-old Kenny Burrell put his Gibson guitar in its velvet-lined case and said goodnight to several members of the Los Angeles Jazz Orchestra Unlimited. He had just finished an intermission-free, two-hour-plus set with the large ensemble, as he has done once a month since the summer. Waiting patiently among the suits and smiles was a 21-year-old guitarist eager to meet his idol. When the room finally cleared, Burrell was amiable and inquisitive, talking to the young fan about music and Michigan, where he grew up. Continue reading