Photo Credit: Goldmic90 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

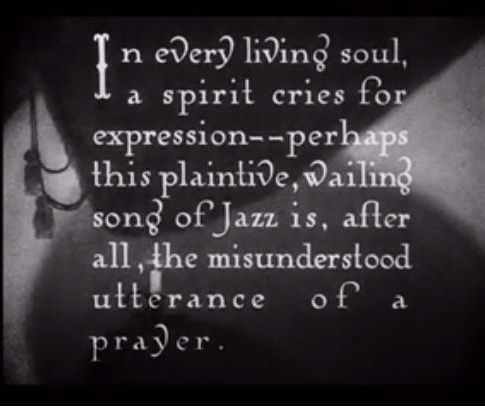

The Jazz Singer

The Jazz Singer premiered on October 6th, 1927. The film, starring Al Jolson, tells the story of a second generation Russian American who wants to become a popular jazz singer. His father wants him to become a cantor in the local synagogue and believes being in show business is sinful. Jolson’s character must choose between his parents’ Russian-Jewish culture and pursuing his dream. The film is controversial today because of Jolson’s use of blackface throughout the film. However, the film is undeniably an important part of American culture because it was the first successful “talking” picture with synchronized dialogue and sound effects. The success of The Jazz Singer pushed all of the American motion picture studios into “the talkies” and effectively ended the age of silent pictures.

Photo Credit: mumblethesilent on Imugr

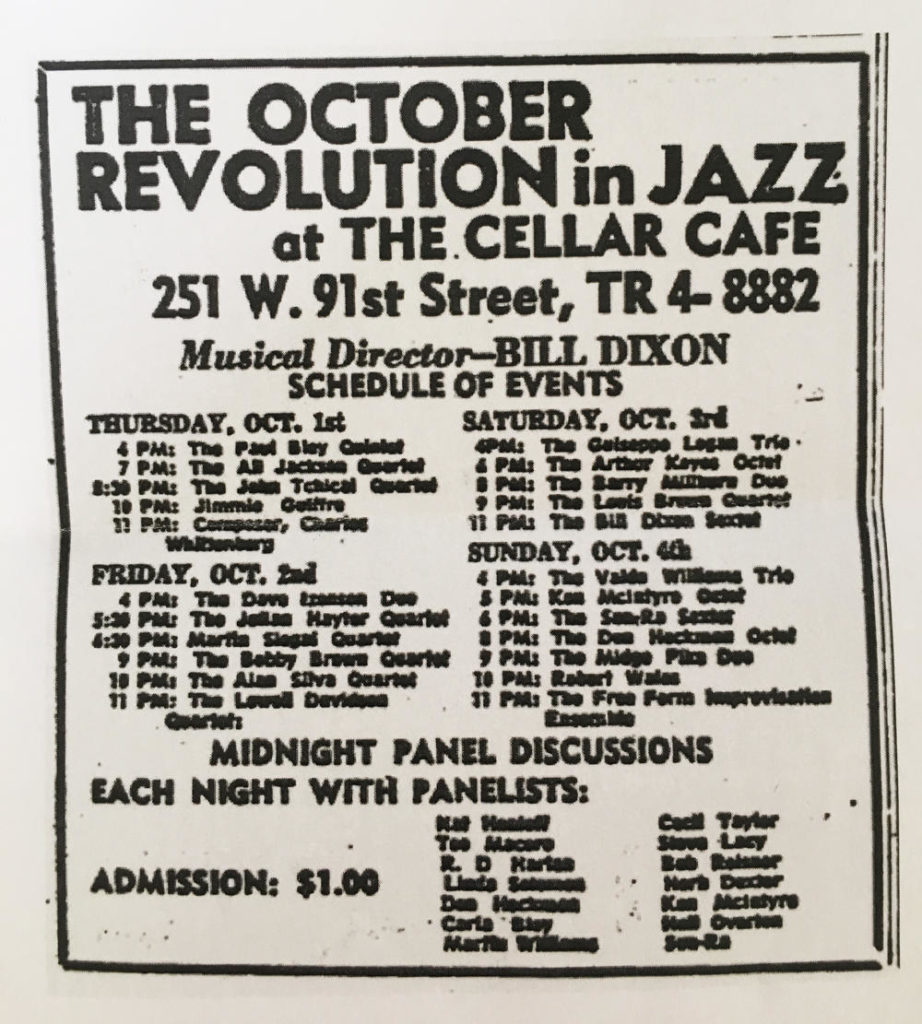

The October Revolution In Jazz

The first Free Jazz music festival took place from October 1st to October 4th in 1964. Organized by musician Bill Dixon, the four day festival had over twenty artists and ensembles performing and discussing their work. Headliners included Sun Ra, Paul Bley, and Cecil Taylor. The festival helped introduce the general public to the free jazz style.

Source: Anderson, Iain. This Is Our Music : Free Jazz, the Sixties, and American Culture. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007. Accessed October 8, 2019. ProQuest Ebook Central, p. 122

Photo Credit: Maureen Malloy